Random walks of a physicist in biology

The personal website and hot takes of Felix Barber.

Research

Bacterial Growth

Widespread antibiotic resistance is increasingly undermining the efficacy of our most successful antibiotics.

Creative and interdisciplinary approaches are required to address this existential threat.

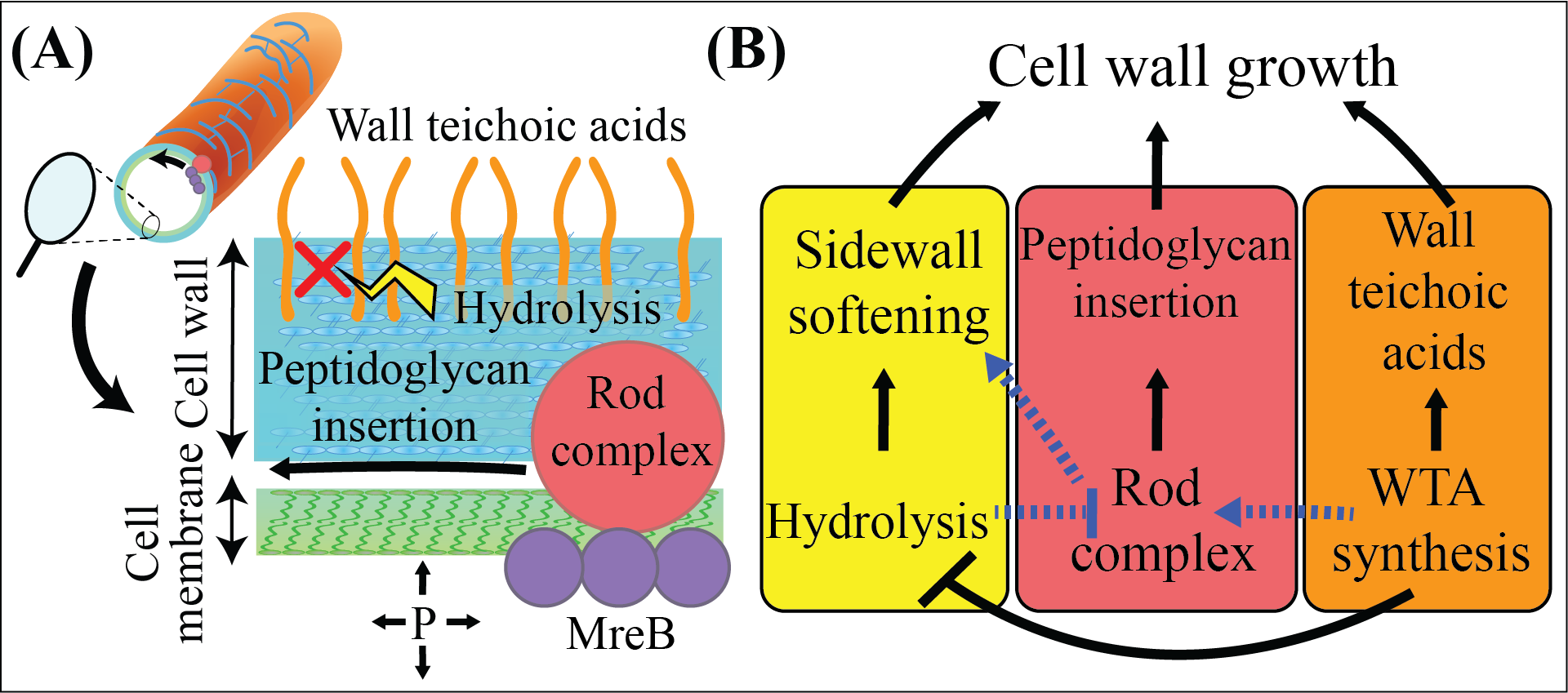

The Gram-positive bacterial cell wall is a rigid structure made of peptidoglycan and teichoic acids that sustains the immense hydrostatic pressure within the cell,

thereby preventing cell lysis. Our best antibiotics target the synthesis of peptidoglycan.

In an exciting development, recent research demonstrated that additionally inhibiting teichoic acid synthesis can reduce resistance to these frontline drugs.

Despite this, our understanding of how teichoic acids influence bacterial cell growth is very poor. My goal is to determine the mechanisms by which teichoic acids

impact the cellular growth rate. Based on my novel preliminary data, my central hypothesis is that teichoic acids serve a critical and overlooked role in governing

cell growth by simultaneously controlling peptidoglycan synthesis and cell wall stiffness, potentially offering a novel avenue to counteract antibiotic resistance.

I am currently constructing genetic tools to precisely tune teichoic acid synthesis, abundance and biochemistry. I will then combine these tools with novel

microfluidics-based assays to measure bacterial cell wall growth, peptidoglycan synthesis and cell wall stiffness to test my central hypothesis in the Gram-positive bacterium,

Bacillus subtilis.

Fig 1: A) Illustration of the Gram-positive cell envelope and Rod complex. B) Illustration of how teichoic acids may impact cell wall growth. Black lines show established relationships, blue dotted lines show my proposed model, wherein WTAs coordinate PG insertion, cell wall stiffness and cell growth.

Fig 1: A) Illustration of the Gram-positive cell envelope and Rod complex. B) Illustration of how teichoic acids may impact cell wall growth. Black lines show established relationships, blue dotted lines show my proposed model, wherein WTAs coordinate PG insertion, cell wall stiffness and cell growth.

Fluorescently labeled Mbl components of the bacterial Rod complex process circumferentially around the cell during growth.

Budding yeast cell size control

My doctoral work furthered our understanding of the mechanism and physiological consequences of cell size control in the microbe Saccharomyces cerevisiae (budding yeast), culminating in three first author publications. Cells from all domains of life regulate their size by coupling their growth and division, however, our understanding of the mechanistic origin of cell size control remains very limited.

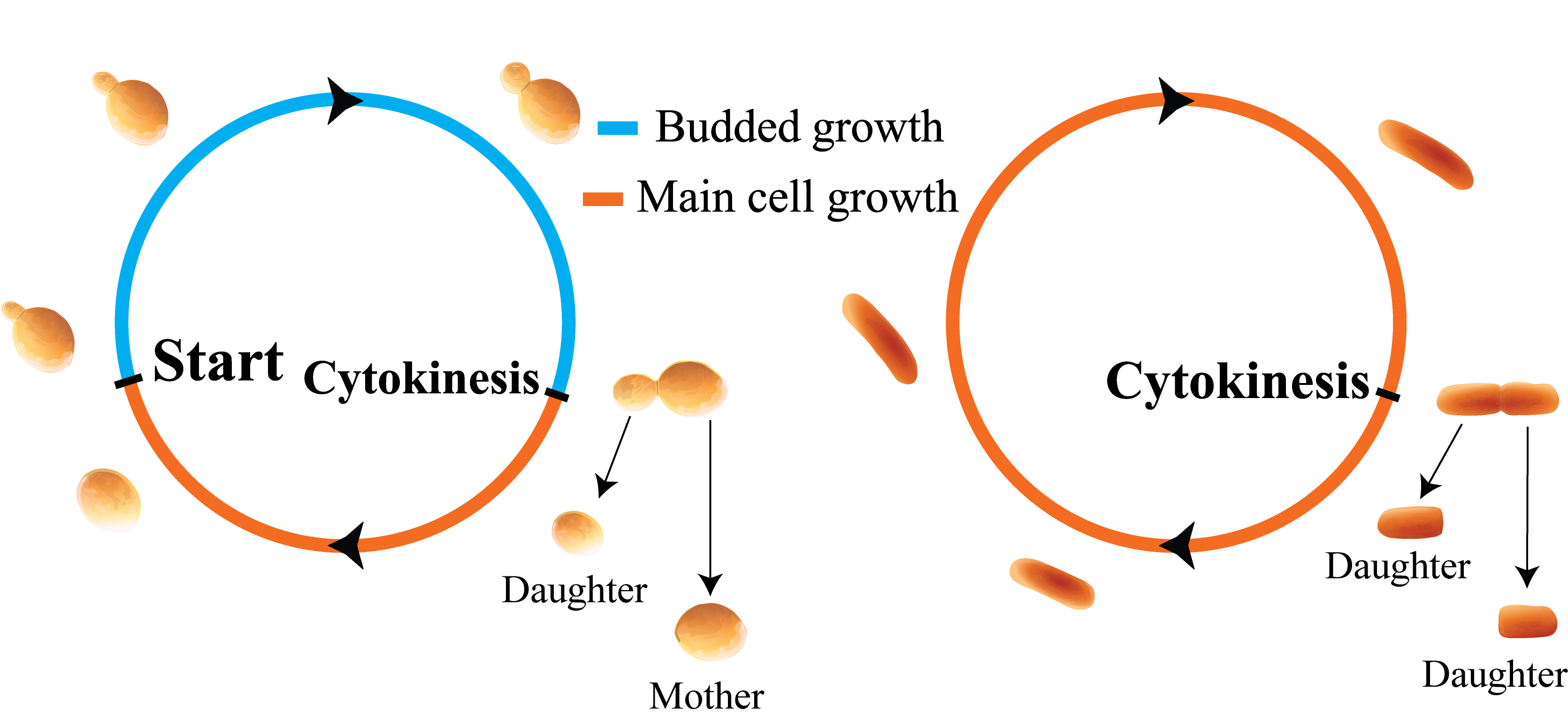

Firstly, I used theory and simulations to study how experimentally observed cell size correlations might discriminate between two phenomenological (non-mechanistic) models of size regulation: inhibitor dilution, and initiator accumulation. We modeled asymmetrically dividing, budding cells (e.g., budding yeast) and symmetrically dividing, bacterial cells (e.g., E. coli), finding that in bacterial cells, an inhibitor dilution model did not robustly reproduce experimentally observed cell size correlations, thereby favoring an initiator accumulation model. Additionally, I discovered a model-independent constraint that symmetrically dividing, budding cells are unable to effectively regulate their size, motivating a novel hypothesis for the evolutionary origin of asymmetric division in budding yeast.

Secondly, I used experimental microbiology to test a widely supported hypothesis for size control in budding yeast. It was believed that linear, rather than exponential, accumulation of the transcriptional inhibitor Whi5 coordinates cell size with passage through the cell cycle transition “Start”. To test this model, I constructed an inducible expression system to make the Whi5 concentration independent of cell size. At a level of Whi5 expression matching WT cells, the size distributions of our inducible strains were indistinguishable from WT cells. I verified this by microscopy using a computational pipeline I developed. The Whi5 dilution model predicts that this perturbation will cause a significant increase in the spread in cell size. I observed no such increase, demonstrating that the dynamics of Whi5 expression are not the fundamental origin of size control in this organism, as previously thought. I also perturbed the expression of Cln3, an activator of Start, disproving another previously proposed model of cell size control based on the Cln3 5’ UTR.

Thirdly, I modeled the population growth rate in asymmetrically dividing cells using theory and simulations. I discovered that asymmetric cell division can enhance an organism’s growth rate in a manner that depends on cell size control, a behavior not previously observed in symmetrically dividing cells. I also disproved a prior prediction that the epigenetic inheritance of cell division times will enhance the population growth rate, showing instead that epigenetically inherited division times can arise as an intuitive consequence of cell size control in asymmetrically dividing cells.

My graduate research combined experimental and theoretical techniques to yield novel insights on outstanding questions in cell size control. My interdisciplinary research motivated a novel, testable hypothesis for the evolutionary origin of asymmetric division in budding yeast, refuted a widely supported model for the fundamental origin of size control in budding yeast, and deepened our understanding of the impact of cell shape and size control on the population growth rate. In each case, my work furthered our understanding of cell physiology beyond the narrow paradigm of symmetrically dividing, non-budding cells.

Fig 2: Illustration of budded vs. non-budded cell growth morphologies.

Fig 2: Illustration of budded vs. non-budded cell growth morphologies.

The BEC-BCS Crossover

This essay on the crossover between the Bose-Einstein Condensate and Bardeen-Cooper-Schrieffer states of matter was part of my assessment for Part III of the mathematical tripos at Cambridge. If you’re interested to see an unpublished literature review from several years ago, look no further! Part III Essay.